Fiction Friday: Sarah’s Second Letter

I’m sharing the historical section of my novel Endless Chain here at Fiction Friday, beginning two weeks ago and continuing today.

I’m sharing the historical section of my novel Endless Chain here at Fiction Friday, beginning two weeks ago and continuing today.

Endless Chain’s story is for the most part contemporary, but the historical section, written as letters from Sarah Miller to the man she loves, Amasa Stone, in far off Petersburg, Virginia, is an important element. The letters are written in 1853, before the War Between the States–known as the War of Northern Aggression by some in the Shenandoah Valley. For your reading pleasure I thought I would excerpt them here.

Endless Chain is the second of five books in my Shenandoah Album series, and it was reissued last spring in trade paperback. However the novel was first released in hardcover, followed by mass market (smaller) paperback.

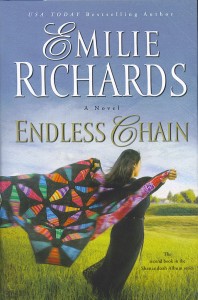

Last week I included the cover of the mass market. The first week I showed you the cover of the new trade paperback. But this week? Well, I thought you needed to see the original hardcover copy, too. And what can I say about this cover that I haven’t already said time and time again to my publisher? They did change it on subsequent books, for which I was very grateful. I do love the Endless Chain quilt, though.

You would think those are all the covers I could show. But stay tuned for the Lithuanian cover next week. Really.

If you missed Sarah’s first letter, divided into two parts, you will find them here and here. And now, the second letter begins.

****

May 25, 1853

My dearest Amasa,

So much has transpired since last I wrote that I am uncertain where to begin. First, I pray this letter finds you and your father well. I have not received a letter in many weeks, but, I know, as often happens, I will receive several upon Jeremiah’s next trip into town.

I no longer feel free to make that journey with my brother. The reason will be clear after I tell all that has happened.

I am sure you remember the story that had just begun to unfold. That night I sat beside the bed of our frail visitor, wiping her brow as fever shook her. Her illness was not unlike the one that took Jeremiah’s family, and I was frightened that I would not be able to affect its course. I was helpless as Rachel and my beloved niece and nephew, succumbed to its evils. Only Jeremiah was helped by my ministrations, and I think he holds my aid against me, for I truly believe he wishes he could have perished with his family.

Dorie Beaumont is very thin, so slight that I feared the worst for her. But by morning she was taking sips of water, and while the fever did not break, it abated. Hope returned to my heart.

Near dawn Jeremiah came into the sick room to see if a new grave would be required. After helping to settle her in my bed he had told me he would notify no one if she died, but bury her on the hillside with our Miller kin where she would be free forever from enslavement or the taint of it.

Jeremiah stared at Dorie’s face, a lovely face even though it is gaunt and sad, and asked the question I knew he would. Why had this woman survived, when his plump, healthy Rachel had not? He does not want to talk of God’s will, even though the words never fly far from his thoughts.

By noon Dorie’s eyes had opened several times, never for long, never with comprehension. But by the time it was necessary for me to leave her and set food on the table (certainly not the large meal Jeremiah is accustomed to) she seemed to be sleeping deeply and comfortably.

I made haste to serve Jeremiah and flew back to the sick room with my own meager dinner on a plate. When I arrived Dorie was sitting on the edge of the bed, the quilt I had rescued from the porch and with which I had covered her, gripped in her hands.

“This is not the quilt,” she said, although I can not properly convey the way she said the words. With little strength, certainly. Her voice was halting and difficult to understand. Not because she doesn’t speak well. (She does. ) But because she was still so very ill.

I bade her lie down, but she would not.

I approached to smooth her pillow and she cowered as if I meant to strike her.

I stood back and assured her I meant no harm. “But this is not the quilt,” she repeated.

“Do you want another?” I asked, in hopes that this simple kindness might calm her. I have many quilts, as you know, Amasa. My mother’s final years were spent stitching them when she could no longer find strength for much else. “I will bring another,” I promised our poor guest. “Only you must lie still and rest so that you will grow strong again.”

“The quilt.” She lifted her hands, the fabric gripped tightly within them. “The quilt. The centers are not black.”

The pattern of that quilt, Amasa, is that of squares surrounding squares. If it has a name, I know it not, being less a seamstress than most women. Each square surrounds one of Turkey red, a red that appears often in my mother’s quilts since this color of poppies and sunsets was her favorite.

Seeking to understand I pointed at a red square around which strips of brown and dark blue sprigged calico cocooned it. “This is not black?” I asked.

“Black. For safety. Black like a starless sky,” she said.

I pondered this and at last, I understood. “You were searching for such a quilt? You were searching for a house with such a quilt hung out to air?”

“Black,” she said softly. “Like night, when it is safest to travel.”

I understood then what she was trying to tell me, or perhaps to tell herself. In the darkness, in the storm, she had come across our home and seen Mother’s quilt draped on the bench across our porch. She believed she had found the house she sought, a house where she had been told she might be safely sheltered.

A house with a quilt of many black squares.

“You have found the wrong quilt, but the right house,” I promised her. “We will tell no one of your presence. We will help you.”

“Are there others here like me?” she begged to know. “Have there been others?”

I was so ashamed my dearest, to tell her there were none, nor ever had there been. We believe not in slavery, Jeremiah nor I. Our church, the same church in which you worshiped, believes it is a sin to hold any man or woman in bondage. Yet we have done nothing to assist our African sisters and brothers. Silently we decry the practice that has brought them to our shores, but Jeremiah and I offer no assistance nor speak out publicly. Some say that war will come of this one day, and perhaps it shall. But I think that had Dorie not arrived on our doorstep, we would not have been tested until war was upon us.

“You are the first,” I told her. “The first of many to come.” As I said this, I knew it must be true and that Jeremiah and I must make it so.

***

Next week at Fiction Friday, the conclusion of Sarah’s second letter from Endless Chain.